As the Major League Baseball season heads toward the World Series, its dramatic conclusion, commentators can be heard chattering about the pitchers whose arms are giving them trouble after a long campaign. Often, the words rotator cuff injury are bandied about, drawing moans and groans from the fans. To them, it raises the fear of potential surgery and the possibility that their favourite player won’t be healthy for the following season.

Should you be concerned when you hear those three words, rotator cuff injury? Let’s define the rotator cuff, discuss exactly what a rotator cuff injury is and consider how it can be treated.

The Rotator Cuff Explained

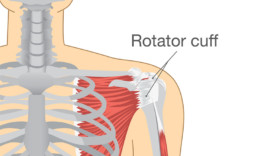

The rotator cuff comprises a group of four small muscles that stabilize and control your shoulder movement. The shoulder is a ball and socket joint, and the muscles come together to form a covering for the ball at the top of the arm bone (humerus) where it fits into your shoulder blade, or scapula.

The rotator cuff is connected to the bone with tendons. To allow the arm bone to glide easily, a lubricating sac called a bursa, separates the rotator cuff from your acromion, the bone at the top of your shoulder.

What Is the Best Treatment for Rotator Cuff Injury?

Impingement injuries resulting from overuse respond well to rest and anti-inflammatory medications. Your physiotherapist may also prescribe exercises to help you heal, restore range of motion and strengthen the muscles. Basic exercises for rotator cuff injury that are often used include:

- doorway stretch;

- side-lying external rotation;

- high-to-low rows;

- reverse fly; and

- lawn mower pull.

Rotator cuff tears can be either partial or full. Partial tears result when a part of the rotator cuff pulls away from its attachment to the bone. They rarely require surgery and respond well to rest, ice, physiotherapy, medication and, perhaps, an occasional cortisone injection.

If the tear isn’t healing despite these treatments, there is now the option of having a bioinductive patch applied to the area using minimally invasive arthroscopic surgery. The patch induces the rotator cuff to regenerate and heal itself.

A full tear means the rotator cuff and its tendon are pulled completely away from the bone. If non-surgical means don’t work in treating your injury, or if your job depends on using your rotator cuff, your physician may suggest surgery to repair it. Generally, a surgeon will reattach the tendon to the humerus bone.

The most common surgical options are open repair, which requires a surgical incision; arthroscopy, which requires a tiny incision and uses a microscopic camera to guide the surgeon; and mini-open repair, which combines the two techniques.

Common Rotator Cuff Injuries

Your rotator cuff is protected from minor bumps and knocks by the bones and the ligaments that create an arch over your shoulder. However, injuries can happen, both acute and degenerative.

Acute rotator cuff injuries result from a single incident, such as falling down onto an outstretched arm or using a jerking motion to lift something too heavy.

Degenerative rotator cuff injuries result from wear over time; they can occur naturally as we age. The blood supply to our rotator cuff muscles and tendons lessens, impairing the body’s ability to repair itself.

Rotator cuff injuries can result from the strain of repetitive motion, making tennis players and baseball pitchers susceptible, as well as painters, carpenters and anyone else who does work overhead.

Common rotator cuff injuries include impingements and tears:

- Impingements result when rotator cuff muscles become irritated, swell and obstruct the space between the arm and shoulder bones, causing pinching and irritation to the tendons and bursa.

- Tears and rips – either partial or full – in the rotator cuff muscles or tendons that attach the muscles to the bones.

What Are the Symptoms of Rotator Cuff Tear?

The symptoms for different types of rotator cuff injuries are varied, but common indicators include:

- an arc of shoulder pain or clicking when you lift your arm to shoulder height or overhead;

- shoulder pain that can extend from the top of your shoulder to your elbow;

- shoulder pain when your arm is at rest (usually seen in more severe rotator cuff injuries);

- shoulder pain when you are lying on your sore shoulder;

- shoulder muscle weakness when attempting to reach or lift something;

- shoulder pain when reaching for a seatbelt; or

- shoulder pain when putting your hand behind your back or head.

A rotator cuff injury is best diagnosed using a diagnostic ultrasound scan. Although MRIs are often used to assess the injury, they have been known to miss rotator cuff problems.

If you are experiencing shoulder pain, don’t hesitate to talk to your physician or your physiotherapist. The sooner a rotator cuff injury is diagnosed and treated, the more likely that you’ll have a complete recovery.